30 June 2014 10 menit

World Leaders Honor Chico Mendes' Fight for Environmental and Land Rights

Monday, 30 June 2014 09:35 By Raven Rakia, Truthout| News Analysis

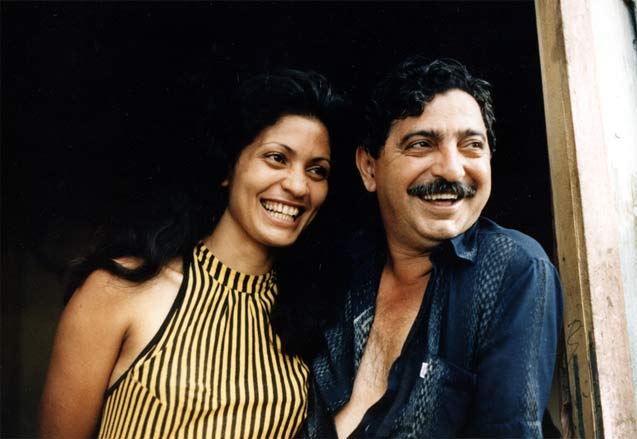

Chico Mendes and his wife, Ilsamar Mendes, at their home in Xapuri, Acre, Brazil. (Photo: Miranda Smith, Miranda Productions, Inc.)

Chico Mendes and his wife, Ilsamar Mendes, at their home in Xapuri, Acre, Brazil. (Photo: Miranda Smith, Miranda Productions, Inc.)

On the first weekend in April, grassroots leaders and activists from all over the world met in a conference room in Washington DC for The Chico Mendes conference, named after indigenous environmental rights activist from Brazil, Francisco Alves “Chico” Mendes, a rubber tapper from the Amazon region, assassinated in 1988 by a rancher.

He joined the fight to protect the Amazon, the environment and people’s livelihoods from cattle ranchers, government officials and large-scale mining corporations – whose profit depends on the destruction of the environment. In one of his most well-known quotes, Chico says, “First, I thought I was fighting for the rubber tappers, then I thought I was fighting for the Amazon, then I realized I was fighting for humanity.” Throughout his life he worked as a rubber tapper, a trade union leader, and an activist before being shot down in 1988. At the conference, environmental activists met from all over the world to discuss tactics and strategy, commemorate Chico’s life and discuss how to continue Chico’s fight.

It’s important to “think about Chico Mendes as a person, not as someone mythical or special” because then “people think they can’t do what he did.”

“Power for power’s sake, money for money’s sake,” asserted Marina Silva as she described what she saw as the core issue of the times we live in. One of the keynote speakers for the conference and former environment minister of Brazil, Marina Silva, spoke with urgency as she labeled the time we live in as “the crisis of our civilization.” The crisis has three parts to it – all of which are structural: economic, political and social. But it’s more than just a mere crisis, “We run a risk of there not being a point of return anymore; that’s what concerns me,” she said during her keynote speech. According to her, we’re currently witnessing “the collapse of our civilization . . . just like the Greeks, Romans and pre-Columbians” eventually witnessed theirs.

Marina knew Chico Mendes from the time she was 17 years old. She describes him as someone whose vision and projects were ahead of his time, but she also believes that he had a legacy that was “projected onto him.” It’s important to “think about Chico Mendes as a person, not as someone mythical or special” because then “people think they can’t do what he did.” She remembers when Chico Mendes was called anti-progress and anti-development for daring to question the effects of development, corporations and resource extraction on the Amazon and the environment.

Leaders Gather From Around the World

Grassroots and indigenous leaders from around the world were in the crowd: Godfrey Massah from Tanzania; Aunty Joan Hendricks from Australia; Edwin Cisco from Liberia; Norman Jiwan from Indonesia; Chief Liz Logan from First Nations (Canada); Cristian Otzin and Ernesto Tzi from Guatemala; Christhian Prado Andrade and Franco Viteri from Ecuador; Tek Vannara from Cambodia; and Hiparidi Top’tiro, Tailey Terena, Raimundo Mendes de Barros, and Gomercindo Rodriguea from Brazil.

These grassroots and indigenous tribe leaders were meeting because they had one thing in common: their interest in protecting indigenous rights and defending the environment, the land and their livelihoods from governments and multinational corporations. Their stories, albeit with many different details and context, sound eerily similar: governments teaming up with multinational corporations, backed by pressure from Western entities, to grab land, deforest and damage the environment in the name of supposed development, investment and innovation.

In Tanzania, orchestrated by government officials pressured by the European Union, biofuel companies are grabbing land from indigenous small-scale farmers and pastoralists, often without their consent or prior knowledge. Godfrey Massah, a program officer at the Land Rights Research and Resources Institute, told the story of Bioshape Holdings and Sun Biofuels. Bioshape holdings acquired 54,000 hectares of land that was originally forest. Before that acquisition, four villages were using and living on the land. The Dutch investors bought the land for $670,000, cut down 10 million trees, and sold the timber for $6.7 million. Afterward, they left, claiming that their company went bankrupt. The result was a food and water shortage in the area. Because the investor had cut down all the trees, villagers were not in a position to use the land, even after they left, and were deprived of access to the land, water and forest – causing many to go hungry.

Eleven villages were living on and using the land when Sun Biofuels acquired 8,000 hectares in Tanzania. When the land was acquired, 700 villagers lost their jobs and livelihoods. Since the acquisition was advertised as an opportunity that would bring jobs, development and food security, many villagers who used the land expected to get employment from the investment. Instead, the chemical-intensive agriculture plan failed – and in addition to losing their livelihoods, villagers lost their access to land they grew food on and to potable water, and the chemicals brought about health complications for those living around the area. Many large-scale agriculture projects that result in land grabs are advertised as innovative strategies that will bring employment and necessary development to the surrounding areas; however, a GRAIN study this year found that “small farms are twice as productive as large farms and more environmentally sustainable.”

Chief Liz Logan, who lives on Treaty 8 land in British Columbia, calls the land, “our grocery store, our pharmacy, our church and our school.”

As Godfrey says, “There’s no way you can talk about land grabs without mentioning World Bank and European Union pressures.” A majority of the time, the EU and World Bank are the ones pressuring governments like Tanzania’s to give the land to foreign investors. The EU’s implementation of harmful policiesthat promote biofuels as environmentally friendly and sustainable result in dangerous practices on the ground in Tanzania. And because of their position in the world economy, Godfrey asserts, countries like Tanzania “are always at the losing end of negotiations” – mainly because of their “lack of financial capacity.”

Of course, Tanzania is not just an exception in the World Bank’s complicity with land grabs. In Indonesia, only after a global campaign headed by Indonesian environmental activists, did the World Bank agree to stop funding palm oil industries . . . but only for the next two years. However, this agreement excludes sugar cane plantations, mineral oil and gas concessions – and the majority of the forests that belong to indigenous people are being threatened with mineral oil mining.

Chief Liz Logan, who lives on Treaty 8 land in British Columbia, calls the land, “our grocery store, our pharmacy, our church and our school.” She discussed the third dam Canada is currently trying to build on the Peace River, which runs through multiple reservations. In the 1960s, when the WAC-Bennet hydroelectric Dam was built on the Peace River, the results included flooded communities, homes and graveyards in the reservations and methyl mercury found in the fish her community eats. Dams can greatly affect the survival of marine and river life – so much so that the river may not be able to support river life at all – with grave consequences for people who depend on a river’s fish for food. Her community is now fighting the third dam, which has already gone through an environmental review and is being built to liquify natural gas on the west coast. But first, they’ll have to get through the indigenous tribes using the land; Chief Liz Logan says, “Some elders who have been pacifists in the past are now saying it’s time to fight, [and] when elders say that, it’s serious.”

At one point, John Knox’s keynote speech was interrupted which a shout of, “Where is the list of the attackers?” by a member of the audience as Knox narrated environmental struggles around the world. “The CEOs of corporations, the government officials, the policemen. I’m peaceful, but a mother has a right to protect her den, and right now our den is getting attacked.”

On the last day of the conference, a workshop, called “Protection For Defenders,” was held. In Brazil, people with interests in capitalizing the land’s resources hire and pay gunmen and private security to shoot and kill environmental activists and “crack down” on indigenous communities.

“When news comes out, it is depicted as one group in conflict with another,” said Gomercindo Rodrigues, a human rights attorney in Brazil, “but usually these things are massacres.” He gave an example in Mato Grosso, where indigenous peoples were assassinated by ranchers who hired private security that were “armed to the teeth. It was not a confrontation, like they say. It was a massacre.”

Fight to Reclaim Land Escalates

Over the past couple of years, indigenous peoples have been escalating a fight to re-claim their land, seizing it from the estate owners. In 2012, when hundreds of indigenous peoples seized their land (that was formally recognized as indigenous land in 2009), gunmen came down on the camp, shooting and kidnapping their leader, Nisio Gomes. In 2013, when indigenous peoples took control of their land once again, federal police and the military moved in and used flash bombs and rubber bullets which resulted in the killing of one indigenous person (along with four injured).

During the workshop, Brazilian organizers discussed how they can’t depend on the state to protect them. After all, Chico was with two police officers when he was shot and killed by a hired sniper. A rubber tapper from Brazil described how he and his community have to take protection into their own hands. He described how he switches up his path at night to avoid people who may be following him. There have been five assassination attempts on his life. The “biggest struggle is not government or the state machinery, it’s quite bigger,” said Godfrey Massah. “It’s a struggle where you don’t see your enemy. You don’t touch him, but he’s there; he’s coming and he’s hunting you.”

Since 1988, the year Chico was murdered, over a thousand land activists have been murdered in Brazil, alone. A Global Witness investigation found that there has been a major surge in deaths tied to environmental activism within the past decade, worldwide. In 2012, environmental activists’ deaths around the world tripled, compared to 10 years before. In the past 10 years, over 900 environmental activists were killed around the world. As Franco Viteri, the president of the governing organization of the Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon, said: “I want to say Chico Mendes’ fight is being waged everywhere. There are many Chico Mendeses in Asia, Africa and the Americas.”

Copyright, Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.